A couple of years ago my good friend, the writer Sara Ryan, did the world a favor when she put together a blog post series called “How NOT to Write Comics.” (Post one, post two, post three.) It’s a useful collection of tips and anecdotes to help aspiring comic book writers, with most of the information drawn (haha) directly from comics artists who have suffered at the hands of inexperienced or incompetent writer-collaborators.

These posts were needed in part because comic books are still not a very dominant medium in the English-speaking world. Travel to France or Japan and you’ll witness a very different culture, where plenty of cartoonists rank in the creative elite, producing work that is both widely read and taken seriously by critics and scholars.

Yet many people in my part of the world still don’t really know how to read comics, much less create them. Sara’s posts provided a useful sort of “Goofus and Gallant” appendix to the ever-growing body literature on how to create compelling and readable graphic narratives.

However, one group wasn’t served by “How Not To Write Comics,” because this group is not interested in writing comics per se. They are interested in writing about comics – or their editors are forcing them to try. Because now that comics have infiltrated the mainstream book trade (and the reading lists of grownups) in the form of graphic novels, memoirs, and trade collections, an increasing number of critics are faced with the task of reviewing the damn things.

The results are, shall we say, mixed.

For every column inch of well-considered and well-informed discussion, there are fifteen yards of lazy, confused, condescending, clueless, unhelpful, and sometimes even frankly hostile copy.

Some of these critics are just jerks who resent that their editor has torn the galley copy of the latest Houellebecq novel out of their hands and replaced it with some stupid book with pictures in it. Pictures. Only Umberto Eco gets to use pictures!

I can’t help those people. I just feel bad for them, because they’re going to miss out on a lot of wonderful and important books.

This leaves all the critics who are just beginning their journey into comics reading, or who have yet to be entirely won over to the medium but want to keep an open mind (perhaps due to peer pressure: I remember a literati cocktail party where somebody near me anxiously muttered “I guess we’re all supposed to read graphic novels now.”) These brave souls are willing to give it a try, but they tend to make a lot of mistakes when they first start out.

Certain errors needlessly recur in comics criticism. Encountering one of them in a critical review or essay is an instant signal to an informed comics reader that the writer doesn’t know what they’re talking about. There might still be some excellent insights on display, but those insights are diminished by sharing the page with outright errors.

Don’t get me wrong: there is plenty of room for interesting-but-still-arguable observations from outsiders, and even room for points best described as obviously-not-true-if-you-know-your-stuff–but-shows-genuine-effort. I don’t want to discourage original thought. But the sorts of mistakes I’m after in this post are not near-misses born from attempts to take on something new. They’re just unprofessional blunders.

Luckily, these mistakes are easily avoided with a little attention. This post is intended to help you, the critic, identify those mistakes in advance so they never hit the page. So, without further ado…I present to you my own personal….

TOP TEN COMICS CRITICISM MISTAKES

#1. Comics Aren’t For Kids Anymore

Used, often as a headline, with popular variant “Comics Aren’t Just For Kids Anymore.” This line is so notorious amongst comics folk that it is often referred to in acronym form (CAFKA).

Here’s the thing: comics haven’t just been for kids since, oh, the 1960s. Underground comics (“comix”) combined counterculture subject matter (sex, drugs, rock and roll, etc.) with some of the artistic techniques from syndicated newspaper cartoons, mid-century horror comics and animation. Virtually none of it is “kid-safe,” although I’m sure many contemporary cartoonists owe their vocations to surreptitious perusal of Mom and Dad’s poorly concealed collections of R. Crumb and RAW.

Furthermore, the sorts of comics that contemporary English-speakers often associate with “kid-friendly” reading – superhero comics – have veered towards an adult audience since the mid-1980s. Did you see The Dark Knight? The Batman movie where Heath Ledger drives a pencil into a guy’s eye-socket by slamming his head onto the table? That sort of thing happens in superhero comics all the time. “Kid-friendly” titles are the exception, not the rule, and it’s been that way since I wore Osh Kosh B’Gosh overalls in size 3T.

So. Stop leading with this phrase; your news story is decades out of date.

As a related sub-genre, I sometimes encounter the critic who gives a comic book a bad review because the comic is (deep breath of smelling salts here) not for children. They are tripping along reviewing this strange little children’s picture-novel when OH MY LORD AND SAVIOR, violence (or worse yet, boobs)!

Certainly, some adult humans will be shocked to learn that they cannot simply pick up a comic book and hurl it at the nearest child. But you’re smarter than that, more sophisticated than that, and you don’t want to waste your precious critical energy on these people. They are too busy being upset about the internet.

In short: some comic books are for kids; some are just for adults. Plenty more will appeal to just about anybody. Comics are a medium, not a toy. The content – not the package – will tell you who should be reading.

#2. “Biff! Pow! Zap!”

Often used in conjunction with “Comics Aren’t For Kids Anymore.” Other, equivalent sound effects are common (SOKK! etc.), and variant headlines or leads include “Holy [insert word], Batman!”

These phrases seem to derive from the 1960’s Adam West Batman TV show, which superimposed lettered “sound effects” during campy fight scenes; the “Holy [whatever], Batman!” was the Robin line that Burt Ward was forced to utter in endless variance. Neither of these phrases have much relevance to actual comic books (Batman or otherwise), and the datedness of the TV show reference is justification alone for avoiding these moldy chestnuts.

And, lest you cling to this language for some illusion of originality or catchiness, a quick Google search for “biff pow zap” turns up ALL of these headlines:

Bang! Pow! Zap! HEROES ARE BACK! – Time Magazine, 1986

Biff! Pow! Using comics to sell health law – Associated Press, 2011

Pow. Zap. Bang. How God makes your action-packed life like a superhero’s. – ChristianityToday.com, 2010

Pow! Zap! Physics? Prof. Jim Kakalios Spices Up Science with a Colorful Teaching Tool – People.com, 2011

and, perhaps most horrifying:

Biff! Pow! Judge Gives Jack Kirby Heirs One In The Kisser In Marvel Characters Ruling – Wall Street Journal, 2011

Likewise, I encourage you to avoid harping on these tired cliches:

- people who dress up in costume at conventions (they’re normal people having fun on their day off)

- the Comic Book Guy from The Simpsons

- anything along the line of “pale guys who live in Mom’s basement”

- any and all unbidden Star Trek or Star Wars references

Don’t go there, friends. We’ve already been.

#3. “With the box-office success of…”

EXAMPLE: “With the box-office success of The Avengers, comic books haven proven their appeal to a wide audience.”

In its most painful incarnation, this sentence will kick off a review of, say, an autobiographical memoir about the artist’s childhood in the slums of Bangladesh.

The point is: movies based on comic book properties are not necessarily relevant to all of comics. (Shocking though it may seem, many comic books have no direct relevance even to other comic books). Would you start a review of a literary novel with the sentence “With the box-office success of Twilight, novels have proven their appeal to a wide audience”? No, you wouldn’t, because (a) it’s patently silly and (b) it doesn’t say anything about the actual work you’re supposedly addressing.

If you must reference the recent blockbuster, a better approach might be something like “while Marvel Comics has sought out a wider audience by adapting its characters for blockbuster flicks like The Avengers, Publisher X has focused on fostering mature, original voices in non-fiction memoir.”

Give it your own spin.

#4. “Non-fiction graphic novel” OR “this isn’t a comic book. It’s a graphic novel.”

This confusion was probably inevitable. The way people talk about comics has changed a great deal in the last thirty years. Let us try to set the record straight! God help us.

Comics (generally singular, despite the s) is the medium. You may also (though much less frequently) hear sequential art.

A comic is any complete work in the comics medium, regardless of genre or length. Rather like “film” or “poem.”

A comic book is, for the sake of definition, any complete work made in the comics medium that is long enough to involve several pages of material or have a collective title. If it were printed, would you have to staple it to keep it all together? Great. Let’s call it a comic book, then.

A graphic novel is a complete work of fiction in the comics form which, if printed, is long enough to be bound as a trade volume, so with a glued or sewn spine. (How’s that for arbitrary?) It is a novel, just as Jane Eyre is a novel, but it is told in comics, not prose.

“Graphic novel” is basically a very clever marketing term that allows booksellers, librarians, and other nervous adults to have a shorthand for “book-length thing of comics that we can sell for over ten dollars and doesn’t make you look like a pedophile for reading in public.” Unlike many people in the comics business, I don’t mind the (fairly new) term, because it’s done great things to convince people who aren’t avid comics readers that it’s okay to pick up a comic book now and again without fearing their book group’s scorn.

When people ask me what the difference is between a comic book and a graphic novel, I say that all graphic novels are comic books, but not all comic books are graphic novels. Then they look confused, and we change the subject.

Hitch #2 inherent to the term “graphic novel” – the word “novel” implies “fiction” which is to say “stuff that didn’t actually happen to anybody.” While I have no sacred commitment to “novel” (since it originally connoted “sordid fad that is corrupting our women and children”), it is rather awkward and confusing to refer to something as a “non-fiction graphic novel” since this translates to “book-length work of non-fiction comics fiction.”

Even more awkwardly, thanks to the multiple meanings of the word “graphic”, if you remove the term “novel” and swap in a more accurate genre description, like “memoir”, you get embarrassing locutions like “graphic memoir” which can be mistaken to mean “prose memoir which involves lots of intense sex and violence.” (The Toronto Comic Arts Festival famously instructs its American guests to avoid using the term “graphic novels” at the border, since many customs agents hear “graphic” and think “pornography.”)

I have no good solution for this one, and nobody else has come up with a consistent reference. Eventually I’d love to hear “comics” replace “graphic” and thus hear about “comics novel” or “comics memoir,” but only time will tell. In the meantime, tread with caution and consult the oracles.

#5. Cartoon(y)(ish)/comic-book(y)(ish)

These words are frequently used, in comics criticism and in criticism in general, as stand-ins for “dumb,” “wacky,” “brightly-colored,” “outlandish,” and “lurid and kinetic with no intellectual or emotional core.” Friends: I challenge you to read David Mazzucchelli’s masterpiece novel Asterios Polyp and apply any of those descriptive terms to it. (Well, it is brightly colored, but there’s symbolism, so it doesn’t count.)

I think it’s fine to use “cartoonish” to describe a simple and exaggerated portrayal. That’s been in use for quite some time, since the heyday of illustration. And obviously the term is also acceptable to explain where on the spectrum of stylization an artist’s work falls – Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi is drawn in a style that is much more “cartoony” than, say, The Killing Joke (drawn by Brian Bolland, written by Alan Moore), which is far more “realistic.”

It’s also fine to use “comic-book-y” to describe a work that intentionally emulates a type of comics work; Lichtenstein, for example, was grabbing directly from comics sources, and there are plenty of movies that draw story and style inspiration from certain kinds of comics.

But it’s foolish to assume that the readers knows WHICH kind of comics you’re talking about. What you really mean is “this work is reminiscent of my personal stereotypes about a medium with which I’m obviously not overly familiar.” And you don’t want to write that, do you? Call out a specific type of comic – “reminiscent of Golden Age Marvel comic books, bright and punchy” or find another descriptor.

In the meantime, if you’d like a more in-depth discussion of the aesthetics and function of visual style in comics, pick up a copy of Scott McCloud’s landmark book Understanding Comics.

#6. Talk bubbles and picture boxes

Would you describe brushstrokes as “paint patches” or a song bridge as “transition verse?” Would you call a fictional plot an “event structure” or a pas de deux a “two-person dance?” No, you would not, because you’re a professional, and you make it a point to understand the terms that define the medium you are concerned with. Nor would you spend overmuch time in a review defining these terms for readers, since it behooves you to assume that they are already interested in what you are talking about (and are capable of looking up terms they don’t recognize).

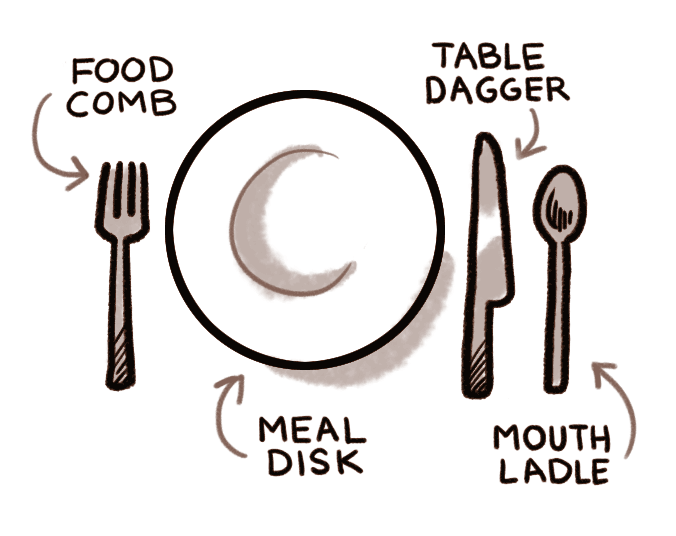

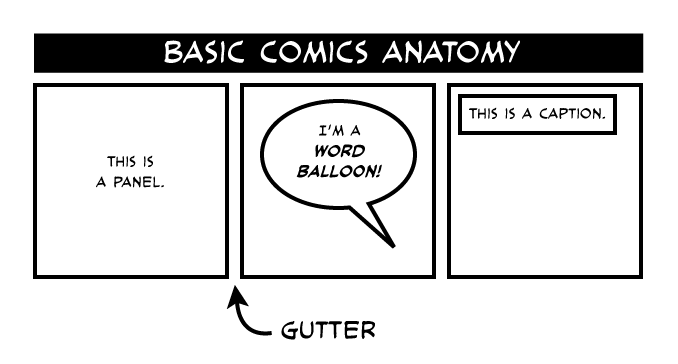

One of the most common errors is to mis-refer to the visual/textual device by which characters in comics traditionally “speak.” These are word balloons. A contiguous chunk of narrative text not uttered directly by a character but instead superimposed over the imagery is typically called a caption. Closed, discrete image units, which generally depict a distinct chunk of time or space – are panels. The spaces between panels are gutters. (Please, no puns; they’ve already been made.)

There are plenty of other terms – including many that are shared with prose and film – but those are the most essential. No neologisms required.

If you’re looking for some further reference on comics vocabulary (and you are), I recommend browsing the following widely-published titles, all of which are appropriate for a general audience:

Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud

Drawing Words and Writing Pictures, Matt Madden and Jessica Abel

The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Creating a Graphic Novel, Nat Gertler and Steve Lieber

#7. This muffin is so good that it’s actually a bagel

Oh, I do love this one, and by love I mean that it can induce me to hurl an otherwise a respectable publication across the room. In this case, the reviewer has been sentenced to read and then write about a comic book. There are two varieties, one seen mostly in smaller, local publications and blogs, and the other in publications of a hoity-toity bent.

VARIANT #1: I Don’t Come Here Often, But…

The first kind of reviewer undertakes her task with a great deal of foot-dragging and exculpatory phrases about how they aren’t “big graphic novel boosters.” Here’s a classic example, from a recent issue of the Seattle Times:

I, like many other rampant bibliophiles, am a reluctant reader of graphic books. Yet, a few pages into Alison Bechdel’s latest memoir, “Are You My Mother?” (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 290 pp., $22), I was hooked despite the comic-book format.

To me, all this paragraph says is “I’m reluctant to try anything that challenges my arbitrary habits, and I’m probably not qualified to review this book in a larger cultural context.” Or maybe (even less charitably) “Oh my gosh, I’m SO not that kind of annoying nerd! Please don’t dismiss my intellectual seriousness for liking this one comic book. If I convince other people to like it, then maybe I won’t feel so uncomfortable!”

I appreciate what the writer is trying to do – reach out to other reluctant readers. (Because that’s what you are in this case, kids: reluctant readers. Not “rampant bibliophiles.”) There’s really something to be said for a “come on in, the water’s fine” approach to convincing the status-anxious to pick up a new kind of book. But you’re not doing yourself or those readers any favors by wincing your way through your appraisal of the work at hand. The most “rampant bibliophiles” I know don’t dismiss a potentially great book just because of its format or genre.

So instead of making yourself look narrow-minded, why don’t you just open your review with praise of the book, as you would for any other title of merit? Then, if you’re worried that people will be hesitant to read on, emphasize that the material has the potential to be both accessible and appealing to prose readers.

VARIANT #2: Green Eggs and Ham

Not all writers are well-intentioned, of course. Some of them see themselves as arbiters of high culture and comics as a party crasher.

This sort of person seems to look forward to writing a vicious takedown. He opens with some flippant references to a legacy newspaper strip like Hagar the Horrible or a sniffy description of the manga collections that his teenaged niece reads in a corner at Thanksgiving while the grown-ups quaff sherry and discuss matters of international diplomacy.

Now that the critic has safely established that he’s not one of “those” people, he brings up the actual comic book he’s been paid to read. To his infinite horror, he finds that it is pretty good.

There will be a few stumbling paragraphs of praise – why, this is reminiscent of fine literature! The pictures and the words combine to create meaning beyond what each individually represents!

And then there will be a stunning piece of rationalization.

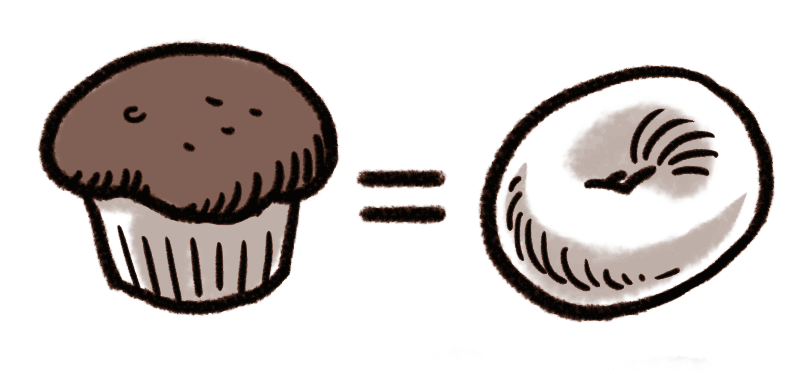

Because this comic book is really good, it must not ACTUALLY be a comic book.

(Or, this comic book is so good, it doesn’t seem RIGHT to call it a comic book.)

There are certainly examples of work that exists to comment on its own form or genre – deconstruction, meta-commentary, appropriation, satire; pick your Trojan horse. It it work that takes on a form just to piss on that form. Every medium has its anarchists, and being able to recognize that intention is a valuable critical skill.

But just because something is better (in your opinion) than many of its peer works does not mean that it is a commentary on its medium, or that the medium ceases to apply. The critic’s assumption that “comic book” connotes “low culture” doesn’t make the work at hand any less of a comic book, or any less of an artistic achievement.

All you’re doing with this kind of rationalization is revealing your own discomfort about liking something you don’t think you’re supposed to. Which is ridiculous. This is comic books, not heroin or blood diamonds or Celine Dion.

#8. Comics: A Bold Artistic Choice for a Cartoonist

The reviewer observes that the cartoonist in question has, in fact, produced something very good, and perhaps not typical of the reviewer’s notion of what a comic book is like. The reviewer acknowledges that the comic book creator is, in fact, a first-rank talent – somebody whose abilities could potentially shine through in other media, as well. (She’s not comic book pretty…she’s literature pretty!)

From this, the critic concludes that the creator is, in fact, making a bold artistic choice by composing her work in this medium. How brave of her – and what does it mean? What is the significance of this choice for the story? Why isn’t it a novel, or a screenplay, which are things that grownups make? If David Mitchell took up macramé the critic would hardly be less perplexed.

The critic will think all these things in apparent ignorance of the fact that the creator in question has been making comics – exclusively comics – for her entire career. She is not a prose novelist in a cartoonist suit for an evening. She is, in fact, a cartoonist. She might be making bold artistic choices within her chosen medium, but comics aren’t a “choice” any more than it’s a “choice” for Steven Spielberg to make a movie.

There are indeed cases where a creator works in several media, and chooses to work in comics for specific story or audience reasons. This is more often true of creators who provide just the writing or just the art and create comics as part of a collaborative team. And some creators genuinely do “moonlight” in comics, as a side venture within a career focused elsewhere.

There’s a simple way to determine which kind of creator you’re dealing with: Google them. Look up their work. Figure out what the comics-to-other-stuff ratio is.

Then decide if what this creator is doing really constitutes a “bold artistic choice,” or merely what she was born to do.

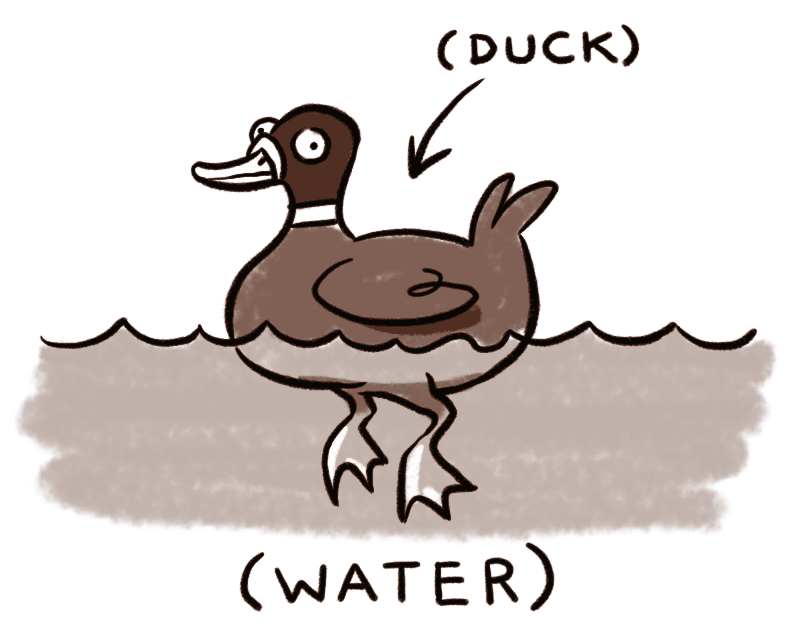

#9. The Unbearable Lightness of Word Balloons

A related genre of critical overreaching. The critic encounters standard elements of comics work – word balloons, square panels, standard layouts – and immediately interprets them as meaningful to the content of the work.

- Comic by Kate Beaton; see on her site, buy on Amazon

This is another example of the critic’s own ignorance coming out to play. Imagine if a critic wrote (of a prose novel) that “the straightness of the lines of text reflect the narrator’s matter-of-fact perception of the world, and the ordering of the letters from left-to-right functions as a subtle reference to his growing political conservatism as he comes of age over the course of the novel.”

This would be silly. Likewise, a painting executed on a rectangular canvas is not automatically assumed to be commenting on the nature of the rectangle. There are plenty of formalist experimenters in comics (pick up a Chris Ware title and watch him go). However, the odds are that the book you’re reading is one of the other 95%, the kind of work that uses standard formal elements as a vehicle for subject matter beyond the borders of the medium itself. The form is meant to become invisible, or at least not draw more attention to itself more than is necessary to enjoy and understand the work.

The only cure for a critic prone to over-analysis is to read enough comic books that it becomes clear when a formal element is routine, and when it’s being used more creatively. Tough break, right? But, in comic books as in everything, you have to walk before you can run.

#10. Poverty of Reference

Another error bred by too narrow a reading list. A critic reads a comic book (“Book A”) and finds some aspect of it striking. The critic has only read one other comic book (B). The critic then adds two and two and gets seventeen: clearly, Book A is deeply influenced by Book B. This leads to a lot of bizarre attributions that seem less like comparing apples to oranges and more like comparing apples to Kevin Bacon. Surely you must see the clear influence that Spider-Man has had on MAUS!

Alternatively, the critic can’t stomach the thought of referencing other comic books at all, or can’t remember even a single one (I once met a graphic arts professor so impressed with himself that he claimed not to have heard of Garfield).

So she spends the entire review talking about nothing but prose work and fine art, etc., as if the cartoonist had invented an entire new medium from the leavings of greater art forms.

Comics in their current form are a tradition dating from the 19th century – like film and the modern novel – but static-words-and-pictures-telling-a-story-in-sequence are as old as words and pictures and nearly as old as sequences. A culture critic expressing wide-eyed surprise that the two things can be combined is kind of like a restaurant reviewer being surprised by sandwiches.

So, yes, Alison Bechdel was very much informed by themes from Proust’s writing when she created her memoir Fun Home. But she also took a lot from Charles Addams, the cartoonist of The Addams Family; she even mentions it in the book itself.

Cartoonists are, in general, not very prejudiced when it comes to their influences. Most of my peers are voracious readers, watchers, lookers, listeners, and players, mostly unconcerned with labels of “high” or “low” so long as the stuff on the menu is good. We don’t collectively put much stock in work that preens over its own elite inaccessibility (having too often been the victims of snobbery in academic settings), but nobody is going to be shunned for liking something and making use of it in their own work. You will quite possibly see the influence of Star Wars and the influence of Ezra Pound sharing a table at your local convention.

But we also come from a rich artistic tradition with plenty to say for itself, and we all owe an explicit debt to the comics creators before us. Their work is our inspiration; their rules and expectations are our challenge.

So you don’t get to pick and choose Alison Bechdel’s influences; Bechdel already did that for herself. The same goes for every other comics creator who strives for original expression. If you can’t acknowledge our full creative heritage, you can’t fully appreciate our work.

Now go forth, to love and serve good books!

So, in review.

If you’re reviewing a comic book, you need to review it in the context of works that are relevant to the one at hand, and you need to make sure that the story you’re telling about it is up-to-date. If you have trouble with this – you haven’t read anything even faintly like this book before and have no idea where it came from, then you need to put in a few hours of research.

- Magical secret #1: comic books are a really quick read. Reading “Great Expectations” will take you twice as long as it would take you to get a quick, serviceable survey of the underground comix movement. Librarians, the internet, your twelve year-old neighbor, and comics retail professionals – to say nothing of the creators themselves, who often have websites and give interviews – will all gladly help in ridding you of that certain je ne sais quoi I’m talking about.

- Magical secret #2: comic books can be truly wonderful. They can also suck. A (very earnest) librarian once asked me how you can tell if a comic book is “good.” I was briefly dumbstruck by the question. I had to tell her that you figure it out the same way as you do with a prose book – you read it, or you read reviews of it, see if it’s won awards or been recommended by organizations, ask friends, see what’s circulating. If you pick up a comic book and you don’t like it – think first “this is probably a bad comic book.” Not “comic books are probably bad.” Can you imagine if a professional acquaintance of yours grabbed a novel at random from the Goodwill book bin and judged all of literature by it?

You wouldn’t be a paid critic if such minor roadblocks as a new genre or a bad book got in the way of your reading habit. It’s your job to tell us, the clueless schmoes of the reading public, if something is worth picking up or not.

When I read a negative review, I want to know what’s wrong with the book, not what’s wrong with your relationship to the medium. Likewise, in a positive review, I’m not looking for a blow-by-blow account of your realization that comic books can have cultural value. I already know that they do; I’m hoping you’ll tell me why this particular comic book has cultural value.

All I want is for you to write a review that I can respect. You can do that by writing a review that respects me, as a reader and a creator.

Because I really need some new reading material. And I’m hoping you can help.

MaggieDreadful

September 18 2012 / 11:55 am

This article is great. I’ve encountered a lot of these cliches just talking to people about comics. I’ve found it very difficult trying to explain to people what “graphic novel” actually means.